Last week, Kaiser Health reported on the difficulty of finding California’s homeless a place to heal and the difficulty of discharging after a new state law requires hospitals to try to find a safe bed with transportation for homeless patients. The article reports that one woman had to sleep in her car the night she was discharged for her double mastectomy.

Last month, The Atlantic reported that rare “medieval diseases” like typhus are arising in California’s homeless population because of poor sanitation and living conditions.

These articles speak to a healthcare crisis that our clinics have been quietly addressing for many years: how do the homeless access healthcare?

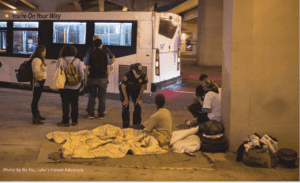

We asked two of our clinics who regularly bring care to the most vulnerable to describe the health risks they see most, and what this crisis looks like on the ground. Both clinics are part of The Street Medicine movement, which advocates for bringing care to the most vulnerable, unsheltered individuals in their own environment- on the street.

In Chicago, NAFC member clinic The Night Ministry has a team devoted to street medicine. Despite having a health outreach bus that travels throughout Chicago, the clinic began a street medicine initiative after realizing that there were still many people they weren’t reaching. In 2018 alone, the Night Ministry served 433 clients, and 155 trips to the emergency room were prevented. In New Orleans, Luke’s House clinic also takes to the streets.

Both programs find that wound care is one of the greatest needs in homeless populations they serve. Wounds come from sleeping on concrete, from injection drug use, from gangrene, and from a variety of other living conditions that also make it difficult to heal. Most homeless can’t wash with soap and water. Living on the streets is, unsuprisingly, not a recovery-friendly environment.

California’s new law is not simply a compassionate solution, but an economically beneficial one as well. If homeless patients are discharged back to the streets, their risk of infection and thus possible readmittance skyrockets.

“Chronic abscesses and skin infections are the most common and quite serious medical issues we encounter….Keeping the wounds clean and properly dressing them can be a challenge for the homeless population. Many often decline to get intravenous antibiotics and more definitive surgical drainage and debridement because they are so terrified of going into withdrawal when they’re admitted to the hospital,” said Dr. Aaron Brinkman with the Night Ministry.

He added that they also see a lot of foot fungus that sometimes progresses into trench foot because of lack of access to basic hygiene and socks.

In addition, mental health care is a critical area of need in the homeless. Luke’s House is working towards a telepsych program that would allow the team to provide mental health diagnoses on the street, which helps people gain housing. Without a diagnosis, patients aren’t eligible for the housing program. But few ever get the diagnosis they need.

The team at Luke’s House also frequently encounters homeless patients with neglected chronic conditions like diabetes and asthma, and no way to afford insulin or inhalers.

“We’re seeing folks who need basic human needs met,” said Adam Bradley, executive director of the clinic.

While the Night Ministry team has not seen any outbreaks of diseases like typhus as the Atlantic did in California, they have seen patients in rat-infested encampments.

“We see a lot of upper respiratory issues with homeless that stay under Lower Wacker Drive, a busy multi-level roadway in downtown Chicago. This is probably due to many different issues, most notably exposure to bird droppings, rat droppings, and pollution,” said Dr. Aaron Brinkman, a member of the street medicine team.

With a new smaller vehicle, they can now travel under viaducts, into wooded areas and encampments. The team includes a nurse practitioner, a case manager, and an outreach worker and is currently seeking an addictions counselor.

Dr. Ralph Ryan, a volunteer physician, described how the street medicine team approaches homeless patients.

“[We approach] respectfully. Their ‘home’ may look different from ours but it is their home, and boundaries need to be respected. Clearly announcing who we are, as The Night Ministry is well identified as a nonthreatening presence, is important. Offering whatever help they may need, listening to their stories if they are willing to share, but perhaps most importantly, coming back and following through on what [we] promise [is critical].”

There’s also a cumulative effect to the work. Gaining trust with one patient can help reach new patients for care.

“We recently helped a client get into treatment and into transitional housing, and now he is helping us connect with others. A lot of the individuals on the streets are skeptical when we approach them. When you have somebody who has been in their place and is now getting back on their feet, and that person can vouch for us, that’s a big plus. He is actively helping us locate new clients and letting them know we are there to help,” said Milton Alvarez, another member of the Night Ministry team.

NAFC believes that healthcare is a human right. But in addition, providing primary care for the homeless saves money for everyone, and protects us all from dangerous public health care crises.

“Street medicine really is important for two reasons. The first reason is that there’s a whole lot of people even in a city as large as our that don’t have access to medical care so we go out and treat people with dignity and treat them as best as we can and try to connect them to long term care,” said Executive Director Adam Bradley.

“The second real reason is that it’s a proven way to reduce healthcare costs for everyone. The people who are living on the street end up in the emergency room when things go bad, and they end up there more often.”

These ER trips have high healthcare and overcrowding costs for all Americans. Homeless healthcare is everyone’s problem.